ANGOR, Northern Ireland - As they say here, even the dogs on the street know the referendums backing the Northern Ireland political settlement that today go before voters, North and South, will pass.

ANGOR, Northern Ireland - As they say here, even the dogs on the street know the referendums backing the Northern Ireland political settlement that today go before voters, North and South, will pass.

Polls show that an overwhelming number of Catholics in Northern Ireland will back the settlement, and that enough Protestants will back it to provide well over 50 percent of the total vote in favor of the settlement.

The critical question is whether a majority of Protestants in Northern Ireland will vote for the settlement. If they do not, the political institutions that will be created under the Good Friday accord could be bogged down by obstructionists who will argue the majority of Protestants do not want them. That could doom the peace process.

If Protestants do vote in favor of the settlement, it will be because people in places like Bangor say yes. As places like Bangor go, so goes the referendum among Protestants.

Located 12 miles east of Belfast, and a world away from the Troubles, Bangor is a prosperous, mainly Protestant, seaside town of some 35,000 that is known for its marina, which is thriving, and its textile mills, which have folded.

The commercial district has been devastated twice in the past decade by huge IRA bombs, but Bangor is a bustling, quaint town that is largely immune to the daily violence and inconvenience visited on poor neighborhoods in Belfast. It is also a town that, if peace takes hold, will benefit from the expected increase in tourism.

Today, Bangor is a microcosm of the Protestant unionist community, those who consider themselves British and want Northern Ireland to retain its union with the United Kingdom. The wealthy play with their boats. The comfortable middle class of police officers, civil servants, prison guards, lawyers and judges, whose jobs are a byproduct of the Troubles, keep the restaurants and shops busy. And on the outskirts of town, where the working class live, loyalist paramilitary groups run the housing projects with an iron fist.

Sandy Rice, 42, was one of the Protestants who in 1974 helped bring down the last serious attempt to return local government to Northern Ireland under a power-sharing assembly. Today, he runs a restaurant, works the door at Jenny Watts, one of Bangor's most popular bars, and sends his son to a Catholic school.

''It's a better school,'' Rice said, shrugging his shoulders. ''It's like this agreement. Having a choice. You have the choice to be who you are, a nationalist or a unionist.''

Rice backs the settlement, saying it will allow for greater cooperation among the Protestant unionist and Catholic nationalist traditions. He also believes it strengthens the union, and that once violence is sidelined unionists will be able to win over more nationalists to the idea that they can express their Irishness and still live in a part of the United Kingdom.

''If nationalists are treated with respect and equality, they'll want to stay in a Northern Ireland that is united with Britain. Not only is there a better standard of living in Northern Ireland than in the South, the fact is we northerners have more in common with each other than with people down South,'' he said.

Rice loathes the two men who are spearheading the campaign against the agreement - the Rev. Ian Paisley, the fundamentalist preacher-politician, and Robert McCartney, a lawyer who leads the small United Kingdom Unionist Party, and who is Bangor's representative in the British Parliament.

''Paisley is a bigot who incited young lads like me to do his dirty work,'' said Rice, who was interned without charge for nine months as a 17-year-old and freely admits he hijacked buses and instigated violence after hearing Paisley's inflammatory anti-Catholic speeches.

''McCartney should know better, with all his education, but he has joined forces with Paisley. Politics is all about compromise. Those boys know nothing about compromise.''

Peter Wilson, 27, would take a different view. A McCartney supporter, Wilson grew up in Bangor, where yesterday he hung antisettlement posters that said, ''It's Right to Say No.''

Wilson is typical of Protestants who object to the settlement not only because it gives the Republic of Ireland a role in governing Northern Ireland, but especially because it will release paramilitary prisoners within two years and allow the IRA's political wing, Sinn Fein, to take part in government.

Like most Protestants, Wilson said he was appalled by the recent temporary release of the Balcombe Street gang, four IRA prisoners who terrorized London with a series of bombings that killed civilians in pubs, restaurants, and subway stations in 1975. The Irish government allowed the men to attend the conference of Sinn Fein, the IRA's political wing, to boost republican support for the settlement.

While the conference voted to abandon republican tenets by allowing its members to take seats in a Northern Ireland assembly, a clear indication that the IRA is willing to let politics take precedence over violence, public attention focused on the outrage over the prisoners triumphantly shaking their fists in the air. The outrage underscored Protestant objections to 400 paramilitary prisoners, split between the IRA and loyalist inmates, being released as part of the settlement.

''Let me ask you,'' Wilson said. ''Would Americans want to release Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber? Because that's what we're being asked to do. Not only release murderers, but to allow them to sit in government. Would Americans agree to that? Then why should we?''

Wilson knows dozens of police officers, and all of them, he said, are voting against the agreement. There are almost 13,000 police officers in Northern Ireland, 93 percent of whom are Protestant and who with their extended families make a formidable voting bloc.

Wilson said a police officer voting for the settlement ''is like a turkey voting for Christmas.''

Although he backs the settlement, David Marin-Pache reluctantly agreed with Wilson. A Dublin-born Catholic married to a local Protestant, he believes Bangor is reflective of the unionist community.

Marin-Pache believes the referendum will pass, but he said he fears that its effectiveness will be diminished by the same people who patronize the bars and restaurants he manages here.

''Bangor is full of police officers, prison officers, judges, people who are understandably worried about their jobs if this thing passes,'' he said. ''A prison officer is literally being asked to put himself out of a job within two years. The police won't be disbanded, and I can't believe any would be just tossed out.''

In separate interviews, four police officers who live in the Bangor area said they strongly object to the release of paramilitary prisoners. Two said they would vote against the agreement, one said he would vote yes, and the other was undecided. All spoke on the condition they were not named.

Yesterday, British Prime Minister Tony Blair made his third visit to Northern Ireland in as many weeks to reassure unionists that he will press the IRA to turn in weapons and will not let Sinn Fein members take their seats if the IRA remains active. And the settlement received an endorsement from Jack Hermon, the former chief of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, the Northern Ireland police force.

''Do I want a normal life? Absolutely,'' one police officer said. ''Do I want to let out those boys who murdered some of my best friends?''

He did not answer his own question. But it's a question that hangs over the unionist community as it goes to the polls today. Are they willing to vote for a chance at a future without widespread violence, or is the past so painful that they feel unable to take a risk on the future?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

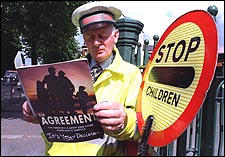

Crossing guard John Rooney looked over the agreement while waiting for children in Belfast yesterday. (Globe Staff Photo / Frank O'Brien)

Crossing guard John Rooney looked over the agreement while waiting for children in Belfast yesterday. (Globe Staff Photo / Frank O'Brien)

ANGOR, Northern Ireland - As they say here, even the dogs on the street know the referendums backing the Northern Ireland political settlement that today go before voters, North and South, will pass.

ANGOR, Northern Ireland - As they say here, even the dogs on the street know the referendums backing the Northern Ireland political settlement that today go before voters, North and South, will pass.