|

The lost boys: Barefoot and starving, thousands of refugee children trekked for years through the war zones of East Africa. This winter "The Lost Boys of Sudan" were resettled in home across Massachusetts and other states. Now their concerns involve matters such as gym socks, "Catcher in the Rye," and the sophomore semiformal.

Dinka values, teenage rites

TEENAGE RITES: Samuel Leek accepts an invitation to dance with Tina Pressey and friends at the Oxford High School semiformal. (Globe Staff Photo / Bill Greene)

TEENAGE RITES: Samuel Leek accepts an invitation to dance with Tina Pressey and friends at the Oxford High School semiformal. (Globe Staff Photo / Bill Greene)

IF YOU WANT TO HELP

The following agencies are soliciting help for the ongoing resettlement of Sudanese young adults in Boston.

Lutheran Social Services of New England still needs foster homes for unaccompanied minors. Contact Karen Santella at 617-964-7220, or contact Martha Mann at 508-650-4400 to send cash donations.

Refugees over the age of 18 are in need of employment, housing, and cash assistance. Contact the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston (Deborah Hughes at 617-625-1920 ext. 301); the International Institute of Boston (contact Christine Hilgeman at 617-695-9990 ext. 156); and the International Rescue Committee (contact Rita Kantarowski at 617-482-1154 ext. 201).

|

|

By Ellen Barry, Globe Staff, 3/19/2001

Second in an occasional series

XFORD - In Mrs. Racicot's second-period geometry class, beside a smart-mouthed basketball player and a bubbly, pregnant senior, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan folded his long legs into an empty seat. XFORD - In Mrs. Racicot's second-period geometry class, beside a smart-mouthed basketball player and a bubbly, pregnant senior, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan folded his long legs into an empty seat.

In Africa, Philip Jok had been known for springing up from the ground like a grasshopper during tribal dances, so that on a good day, his bony feet flew up to his friends' heads. He was famous for writing long, extemporaneous songs about cattle.

But at Oxford High School on Jan. 18, all that receded into the past as he was issued a paperback copy of George Orwell's ''1984,'' a three-ring binder, and a combination lock. During the course of that day, he would stare blankly through a class discussion on the last days of the czarist regime in Russia. He had not been informed of Communism's rise, or its fall, until that morning.

And later, in the gymnasium, he would sit on the bleachers as primly as a missionary, collar buttoned, while eighth- and ninth-graders raucously shot baskets in front of him. He had ''never seen such a kind of place,'' he said, or ''put that ball in that pocket.''

But that didn't matter, either, when he got up and loped across the squeaking floor to the basket. The freshmen, cheeks burning, watched mutely.

''He skies,'' said Bobby Martin.

Philip Jok has a jump shot.

In moments like this, in classrooms across eastern Massachusetts, Jok and 50 other Sudanese teenagers who arrived three months ago are crossing a divide from a desperate childhood to the protected zone of American adolescence.

When the young men known as the Lost Boys of Sudan came to the attention of aid workers in the early 1990s, they presented a terrible image: a river of thousands of male children removed from their homes in the chaos of Sudan's civil war, rail-thin and often naked, who had walked hundreds of miles in scorching heat.

They grew to the brink of adulthood in African camps, and remained so cut off from the outside world that their journey to America, where the State Department is resettling 3,800 of them, seems a trip not just across continents but through time. When they left their mud huts for the last time three months ago, many had never heard of the moon landing or the atomic bomb, or, according to a spokeswoman for the Lutheran Social Services resettlement program, ''what stairs were for.''

Throughout the process of resettlement, they have repeated their shared goal so many times that it has begun to sound like a prayer: to learn enough to return to southern Sudan and lift their people out of their pre-modern state. Eighteen-year-old Bol Thiik strode into Winchester High School with a fully formed idea of what he needed. He sat down with the principal, Susan Morse, and requested instruction in ''religion and agriculture.''

Months later, the closest he has come is ''Catcher in the Rye,'' the classic text on the American teenager's search for meaning. For that, as for social studies, tank tops, and the overhead projector, the boys from the Dinka tribe were totally unprepared.

It is a gap that can't be crossed gradually, said Ambrose Beny, 63, a Sudanese-born professor of English literature who, like the boys, grew up in the world of savannah cattle-herders, and then moved to a small town in New Jersey through an exchange program.

''The thing I like about America is that it does not leave you alone,'' said Beny, who first came to America in the 1960s. ''You cannot be neutral about it. How you adjust and adapt to it, that's the real question. Some, of course, will get lost, because they won't make the transition.''

How these boys will be changed by living here is anyone's guess, he says, but one thing is certain: They will be changed.

''Give them six months,'' he said. ''Let America do its work.''

Livin' la vida loca

In the Ethiopian camp where Bol Thiik learned to read, there was no paper, so the boys sat in long rows scratching letters in the dirt with sticks. The children were caned if they moved, so they learned to sit for hours on their knees in the sun, naked or nearly naked. Dust was a problem, said Thiik; if it was thick enough that drivers had to turn on their car headlights, school was canceled. In long rows, the little boys learned to repeat and memorize lists of facts.

The schools in America were indoors. There were many classrooms stacked on top of each other. The boys realized, after a few days, no one was being caned.

And suddenly, for the first time in their education, part of the subject matter was themselves.

''Commit to working on two or three of your favorite character traits over the summer,'' advised one guide for new students at Oxford High School, and Winchester's contained the following advice: ''Q: Some people say your friends will change in high school. Is this true? A: From our experience, you tend to grow apart from some of your middle school and elementary school friends, but it is totally natural.''

The boys' concerns were more basic. Trained to address their teachers as ''master'' and ''madam,'' they were astonished and dismayed by American students' casual insolence toward adults. And they were unnerved to see boys and girls kissing in the hallways. Romantic yearning is not a central value among the Dinka, who buy their wives for cattle and sometimes marry four of them. Speaking to a girl in school, or on the roadside, is grounds for punishment, and a young man wishing to talk at any length with a girl is required to arrange it through her parents, Thiik explained.

Those Dinka values met their biggest challege to date at the Oxford High School Valentine's Dance. Jam'n 94.5 emceed, which meant ''Livin' la Vida Loca'' and the Bloodhound Gang singing ''You and me baby ain't nothing but mammals/Let's do it like they do on the Discovery Channel.'' The four Sudanese boys had been wondering for weeks just how the Americans dance, and they stepped into a cafeteria strangely swimming with spotlights.

What they saw was astonishing. They paused, trying to figure it out.

''We were just waiting for the organization of the party,'' said Alith Ayuen, an 18-year-old with ghostly tribal marks on his forehead. ''I saw people dancing and I thought, how are they going to organize that? They told me it is already started. Then we went to the field and danced.''

Weeks earlier, the first Dinka venture into the bass-pounding crucible of the high school dance had ended badly. Among the hundreds of teenage boys who were brought into the country before Christmas was a much smaller group of teenage girls, including Aduei, a tall 17-year-old who stands perfectly straight. At her first dance, a classmate drew her so close to him that she tore away in the middle of the dance floor.

''I thought I would lose my culture and I became frightened and I ran away,'' she said.

At their own dance, a similar moment arrived for William Wol, Samuel Leek, Philip Jok, and Alith Moses. The music slowed, and girls stepped out of the crowd to pull them close.

''The girl who was dancing with me, she came and hooked me like that,'' said Ayuen. ''I think about whether I can just push her back or I can continue. And one of these people were just glancing, watching us.''

After the dance was over, they shook their heads disapprovingly over the girls' scanty clothing, which seemed far more provocative than the occasional nakedness of their home villages. Said 16-year-old Samuel Leek, thinking back on his schoolmates at the dance, ''They pretend that there are clothes, but there are no clothes.''

The boys went into gales of laughter recalling it; it would be wrong to call them traumatized by the event. In fact, by the time the strobe lights went off at 11 p.m. and the cafeteria returned to its former life as a cafeteria, Moses had won a box of chocolates in the dance contest.

They came home dazzled by the crazy freedom of American teenagers, restless, excited, with a hundred things to think about - as Leek put it, ''somehow happy but not happy.''

`They don't know the Earth goes around the sun'

Three months ago, when the boys climbed off a plane into a world glazed in ice, they could hardly think beyond the pure physical shock. Their skin seemed to be shrinking; they felt that their hearts were unprotected from the cold. On his way to the bus stop on the blue, crescent-mooned morning when he was to start school, Philip Jok still marveled: ''I feel my hand not to be my hand.''

But when school began, the stress shot off in a different direction. Carlos Akot complained to his teacher that his brain had begun to hurt.

Jolanta Conway, the dimpled, Polish-born ESL teacher at Winchester High School, was watching 18-year-old Akot as he struggled through a standard high-school English text: Ray Bradbury's chilling, futuristic story ''There Will Come Soft Rains,'' which describes a day in the life of a house whose occupants have been burned away by an atomic blast.

Conway knew by the dismay on Akot's face that something was terribly wrong.

She rushed to assure him that none of it was real.

''I tried to explain, `When you were children, you were imagining things. It wasn't real. This is the same way,''' Conway said. ''They asked, `Why do people do this? Why do people write something that is not true?' Then they were reading science fiction, and I thought, `Oh, my God.' ... I told my husband, `My brain is hurting, too,' because I had never analyzed a short story like that.''

How do you teach a 17-year-old the concept of fiction? Their needs, teachers found, were not quite the same as English-as-a-Second-Language students; most speak stilted, archaic English passed on from missionaries. Nor were they ''special needs'' students, exactly; many are not only smart but desperately motivated.

They were something else entirely - unaware of basic facts about the modern world, like ''someone who has lived out in the woods for 50 years, and then come back,'' said Kathy Threadgould, who teaches computer science and math at Oxford High School. Early on, one of her Sudanese students asked her why words didn't come out of the mouths of people in photographs.

For months, teachers kept discovering new gaps. At Winchester, two of Conway's Sudanese students finally confessed the heart-racing terror they experienced every time their foster parents drove over elevated highways, which they feared would collapse and kill them.

In Oxford, a tutor organized a trip to a costume shop, to prove to her incredulous students that Barney was not a real talking animal.

''I saw there on TV a cow can speak English, and a dog can also speak English,'' said Jok, with an amazed laugh. At the costume shop, ''all those things, we saw them there. They can just have leather, and they can wear that leather, and you will be seen like an animal. If you are seen in our country, they can say, `Oh, that is a god.'''

''Me myself I believed them,'' he said, ''but nowadays I never believe them.''

To some who worked with the students, those early days were spellbinding. In math, for instance, where they were initially assessed at an eighth-grade or lower level, the students were picking up new concepts incredibly fast, ''doing something symbolically that I wouldn't have thought possible,'' said math teacher Richard Thorne.

''It's interesting to watch how a mind absorbs something,'' he said. ''It's like a tabula rasa.''

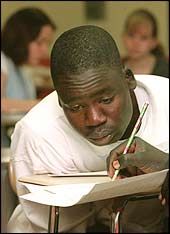

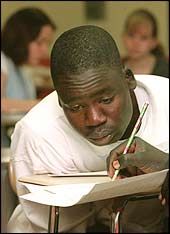

MASTERING ALGEBRA: David Lual studies at Winchester High. (Globe Staff Photo / Bill Greene)

MASTERING ALGEBRA: David Lual studies at Winchester High. (Globe Staff Photo / Bill Greene)

|

But at other times, they just seemed painfully dislocated. Four of the Sudanese began classes at Boston English High School, which has so many African immigrants that it offers a bilingual track in Somali. Shortly after they arrived, one teen went to a tutor, Paul Siemering, seized with anxiety over his lost his lunch card. Siemering carefully explained that it was nothing serious. Then he took him back to the cafeteria, where a worker explained that she could make him a new card. But the next period, Siemering walked into the library and found the young man with his head down on a desk, sobbing.

''These boys are more culturally and socially deprived than anyone who's ever come in here,'' said Siemering, who has been tutoring African students at English for 10 years.

''It's almost impossible for regular teachers to grasp their level of innocence,'' Siemering said. ''They don't know the Earth goes around the sun. They don't know who Elvis Presley is. They don't know who Hitler is, they don't know World War II. You might as well be talking Sanskrit. It's hard to go far enough back to start.''

Three months into their journey, though, something has started to happen.

David Lual had announced his intention to return to his home village, marry five wives, and herd 500 cattle. Then suddenly he mentioned that he would also like to visit Venice. In the Arlington group home set up by St. Paul Lutheran Church, William Wol, a nearly wordless 18-year-old who lovingly drew cattle in his school notebooks, began dinging on piano keys with a tentative finger.

And Alith Moses - whose home village is still so cattle-centered that paper currency is worthless - started to like the poetry of Edgar Allen Poe. He even said he would consider marrying an American girl if ''the kind of relationships that is happening between me and her is very strong, that is like what is happening in that poem `Annabel Lee.'''

`I can't come home anymore'

Whether or not the boys know it now, there are certain kinds of information that change you permanently, said Ambrose Beny, the professor who was among the first Dinka to receive an education in the West.

''I can't come home anymore,'' said Beny. ''In some ways it would probably be too limiting for me. There are not too many [Dinka] - I mean, there are none of them - who have read Shakespeare or William Faulkner. And I would want to talk about those writers, so in a way, I would be lost.''

In the high schools where the Sudanese boys spend their days, other shifts have taken place without anybody's notice. At Oxford High School's sophomore semiformal, to the accompaniment of Sir Mix-a-Lot's ''Baby Got Back,'' 16-year-old Cassandra Rose flushed with pleasure recalling the letter she had received, through an intermediary, from one of the young Sudanese men.

Eyes ringed with the palest blue glitter, Rose wore a pink feather bracelet and decals on her fingernails. She had instantly related to the displacement of the Sudanese students, she said, having transferred to Oxford from Worcester herself.

The note melted her heart with its courtly language, although she had to look up some words, like ''consort,'' and she wondered why he kept referring to her as ''obedient girl.''

Still, in a high school where male gallantry runs along the lines of ''I-think-you're-cute-do-you-like-me,'' she said, there was something strange and wonderful about the words he used.

''Do not worry about me a lot,'' the note said, ''but I will always be the first one to worry about you.''

At the request of resettlement workers, the last names of the boys have been omitted throughout this article.

This story ran on page A1 of the Boston Globe on 3/18/2001.

© Copyright 2001 Globe Newspaper Company.

|

![]()

![]()

XFORD - In Mrs. Racicot's second-period geometry class, beside a smart-mouthed basketball player and a bubbly, pregnant senior, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan folded his long legs into an empty seat.

XFORD - In Mrs. Racicot's second-period geometry class, beside a smart-mouthed basketball player and a bubbly, pregnant senior, one of the Lost Boys of Sudan folded his long legs into an empty seat.