aia latches onto Tierney's breast, her eyes rolling back in sleepy serenity, her body more relaxed with each sip of milk.

aia latches onto Tierney's breast, her eyes rolling back in sleepy serenity, her body more relaxed with each sip of milk.

''Yes. You're a good eater, Nai-nai,'' Tierney whispers, cradling her baby on their living room couch.

Greg is setting the table for a takeout Chinese dinner. A small Christmas tree waits expectantly nearby; snow flurries brush against the apartment window; a jazz CD plays softly.

But this is no blissful family tableau.

Naia's skin has a distinctly yellow cast. Tierney's mouth is a tight line. Her eyes are red and her neck muscles dance under the collar of her white turtleneck. Greg is unshaven, funereal in all black clothing.

During the 10 days since she came home from the hospital, Naia has stubbornly failed to thrive.

It is Dec. 14, 1998. Naia is 22 days old and weighs 5 pounds 14 ounces, just 2 ounces more than her birth weight.

Her damaged heart is struggling to pump enough oxygen to the rest of her body. Her liver isn't working properly. She's brewing a urinary tract infection. She is sleeping too much, eating too little. Her system is so fragile that a cold could kill her.

Having decided to continue the pregnancy knowing their child would have Down syndrome and a heart defect, having soldiered through the difficult birth and frightening first days of Naia's life, Tierney Temple-Fairchild and Greg Fairchild are finding that the problems keep piling up. More even than they had allowed themselves to imagine.

''We're in that grind of always worrying that there's something else we need to worry about,'' Greg tells Tierney.

And there is good reason to worry. With each passing day, Naia's body is in a more urgent race with itself.

Despite weakness and lethargy, Naia needs to quickly gain enough weight to survive the heart surgery she needs for a chance at a healthy life. If she gains the weight, she can win the race. But if her heart begins to fail before she is strong enough for the operation, the surgery itself might kill her.

* * *

The first goal in Naia's life is deceptively simple: 8 pounds. That is how much doctors believe she should weigh before they risk opening her chest to repair her heart.

Eight pounds is within the normal weight range for newborns, but it seems months away for Naia. Now, with Naia's growth rate stalled, Tierney and Greg face difficult new choices.

First among them is whether to end breast-feeding and switch exclusively to a bottle, using breast milk Tierney collects with a suction pump. Already, when Greg feeds Naia breast milk from a bottle, she finishes more quickly, is less tired afterward, and seems to drink more than when she nurses directly from Tierney.

Naia's pediatrician, Dr. Della Corcoran, has even begun dropping hints about ending Naia's reliance on breast milk altogether, switching her to a high-calorie formula more likely to hasten weight gain.

Greg and Tierney want to do what's best, but it seems odd that breast-feeding -- usually the best choice for babies -- might be placing Naia at greater risk. It is particularly hard for Tierney. She was eager to breast-feed, believing it would help Naia flourish, despite the mental retardation and physical disorders of Down syndrome.

''She's getting a bonding experience from me, which I love and I'm sure is good for her,'' Tierney says. ''But why am I doing this if it comes at the expense of her gaining weight, which I know is the most important thing right now?''

Sighing, she adds, ''It's just all so hard.''

The question of breast milk or formula will haunt them for several more weeks. But it is not the only challenge that Naia, Tierney, and Greg face on the road to 8 pounds.

* * *

Eight days later -- Dec. 22 -- Naia is one month old. A visit to the doctor takes the place of a celebration.

While waiting to see their pediatrician, Greg and Tierney sit with Naia in the waiting room and listen to a mother laughingly complain about how big and heavy her daughter was at birth. Her baby is the same age as Naia, but twice the size.

Greg and Tierney offer the woman wan smiles but say nothing. Comments about Naia's size -- ''Is she a preemie?'' -- are common on the infrequent occasions when Tierney and Greg expose Naia to the world, where the winter cold and potential for illness must be avoided at all cost.

Things only get worse inside Corcoran's office. The doctor delicately places a squirming Naia on a counter-top infant scale. Greg and Tierney watch intently, barely breathing.

Naia is 5 pounds 14 ounces. No change in more than a week. Tierney throws her hands up in frustration.

This means the end of pure breast milk. Tierney can nurse Naia twice a day, Corcoran says, but four other feedings must be from a bottle of breast milk mixed with a formula called Pregestimil.

Corcoran explains that Naia's slow growth is most likely a result of her heart's failure to pump enough oxygen-rich blood, without which her body lacks the fuel it needs to gain weight. The formula should boost her growth despite the heart defect.

Tierney is upset but tries not to show it. She realizes the most important thing is that Naia get those calories. She dutifully records Corcoran's instructions in a small brown notebook she has begun carrying to keep track of Naia's lengthening list of medical problems.

Corcoran also notices that Tierney and Naia share a common yeast infection called thrush -- on Tierney's breast and in Naia's mouth. She prescribes an antibiotic called Nystatin. Naia needs it four times daily; twice a day for Tierney. Again, Tierney writes it down in her book.

Since last week, on orders from her cardiologist, Naia also has been taking a heart medication called Lasix. Defects such as Naia's -- a hole between the chambers -- can lead to a buildup of salt and fluid in the body, which compounds heart problems. By encouraging urination, Lasix helps to improve heart function.

During the examination, Corcoran adds an unintentional insult to the injury of Naia's newly diagnosed ailments. Corcoran refers to her as ''my little peanut,'' and Tierney recoils.

''What's the matter?'' the doctor asks.

''We don't use the word `peanut' for her,'' Tierney says, calm but cool. She tells Corcoran the word has negative racial connotations, particularly in the South, where Greg grew up.

Corcoran says she calls all her infant patients peanut, but apologizes and says she won't refer to Naia that way again.

The doctor punctuates the visit by saving the worst news for last: Naia is jaundiced, a clear sign of liver problems and the cause of her yellowish skin tone.

Jaundice is not uncommon among newborns, regardless of whether they have Down syndrome or a heart defect. Sometimes it's related to breast-feeding and clears up on its own. But there's another kind of jaundice that is potentially lethal.

Instead of returning home as planned, a discouraged Tierney and Greg drive to Connecticut Children's Medical Center. There, Naia must undergo blood tests to check her liver function.

Before the tests, Greg and Tierney go to the hospital pharmacy to fill her new prescriptions. While they wait, a little boy walks over to them. He has an awful, hacking cough, but his mother does nothing to draw him away from Naia.

Tierney looks to Greg with pleading eyes, fearful that -- on top of everything else -- Naia will catch a deadly germ.

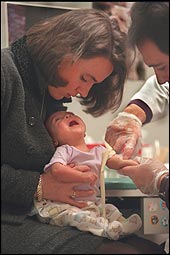

NAIA LOOKS TO HER MOM for comfort while a technician struggles to find a vein to draw blood two weeks before Naia's open-heart surgery.

NAIA LOOKS TO HER MOM for comfort while a technician struggles to find a vein to draw blood two weeks before Naia's open-heart surgery.

(Globe Photo / Suzanne Kreiter)

|

''Don't worry,'' Greg says softly, shielding Naia as best he can until the boy leaves. ''He was far enough away.''

Tierney nods, but her face betrays her stress.

Medicine in hand, they go to a small room on the hospital's second floor that is gaily decorated with hanging mobiles and cartoons of Barney and Tweety Bird. A nurse has trouble finding a vein from which to draw Naia's blood. Naia screams. Tierney winces.

As they wait for Naia's cries to end, they notice a poem pinned to the back of the door, placed there by a hospital worker whose son nearly died. Shoulder to shoulder, Greg and Tierney read its rhyming couplets. The closing lines read:

''We'll love him while we may...

But shall the Angels call him

Much sooner than we planned,

We'll brave the bitter grief that comes,

And try to understand.''

Finally, Naia's blood drawn, they scoop her up, hold her close, and bring her home.

* * *

Since Naia's birth, medical problems and routine care have dominated Greg and Tierney's time and thoughts. Naia's first Christmas is a low-key affair. Gifts run along the functional lines of baby clothes and a bottle sterilizer.

Yet in the quiet moments between feeding, diapering, medicating, and sleeping, they reflect on the decision they reached nearly five months ago. The discussion is triggered when Greg finds a Newsweek magazine lying around the house. It's long out of date, from March 22, 1997, but they had never read it.

Deep inside Greg notices an article on birth defects and prenatal screening. It contains this line: ''Down syndrome in theory is completely preventable, in the sense that there is a reliable test for the extra chromosome known to be its cause, after which the pregnancy can be terminated.''

Greg and Tierney know that, but the next line comes as a shock: Among women who learn they carry a fetus with Down syndrome, about 90 percent abort. At last, they have an answer to the question Greg had tried to ask their obstetrician, Dr. Michael Bourque: ''What do people do?''

''There's no changing our decision, not that we'd even want to,'' Greg says. ''But 90 percent? It's human nature when you do something to look around and see what other people have done. But to hear that you're so in the minority....

''You have to wonder,'' he adds, ''what do the other nine people know that we don't?''

It dawns on Tierney that, based on the 90 percent figure, nearly everyone they've told about their decision would have made the opposite choice. It's also possible that some people they've told actually faced the decision and chose abortion.

''That shouldn't surprise you,'' Greg says. ''You probably wouldn't do the same thing that 90 percent of other people would do in most cases, anyway.''

Tierney smiles and thinks about their decision to marry across racial lines. ''Well, I guess that's true about both of us.'' Greg smiles back.

* * *

It is Jan. 14, 1999. Naia is nearly eight weeks old and weighs 6 pounds 8 ounces. She has gained 12 ounces since birth, 10 in the past three weeks, the result of orders by Corcoran to add even more formula to her feedings. Eventually, the formula will be mixed as thick and rich as a milk shake.

Still, Naia is a pound and a half away from her goal, and time is growing short. Surgery is needed sooner than expected.

Naia's heart is barely keeping pace with her body's hunger for oxygen. To compensate, she takes deeper and deeper breaths. With each one, her skin sucks up and under her ribs, making her chest look like a child-size xylophone.

Naia's cardiologist, Dr. Harris Leopold, has been teaching Greg and Tierney to look for signs of congestive heart failure, in which the heart is unable to pump blood with enough force to the body. One sign is a bluish tint to the skin.

Greg and Tierney always expected they and their child would be aware of black and white. Now, they also have to worry about the yellow of jaundice and the blue of heart failure. To top it off, a fifth skin color has entered the mix: pink.

Just before Christmas, Tierney took a picture of Naia to a photo shop across the street from their apartment to order reprints for faraway family and friends. A few days later, Greg picked them up and brought them home.

''Greg, they lightened Naia's picture!'' Tierney fumed when she saw the results. ''She looks a lot whiter than she did in the original.'' She marched across the street with the original photo and confronted the man who had taken her order.

''I don't understand why you did that,'' she said.

''I'm sorry,'' he said sheepishly. ''I just looked at your complexion and figured that she would look like you. It's just that most babies are pink, so I made her pink.''

''She's not pink,'' Tierney said.

He agreed to redo them. No charge.

* * *

During the early weeks of the new year, Naia's heart remains a priority, but her liver problems have begun causing even bigger fears. The source of her jaundice remains a mystery.

Two weeks of near-daily visits lead Naia's liver specialist, Dr. Jeffrey Hyams, to conclude that Naia has one of the more dangerous types of jaundice. He suspects it's either a blockage in the tubes that connect the liver to the small intestine, or an inflammation of the liver called neonatal hepatitis.

Hepatitis can be treated with drugs, but a blockage likely would require surgery. There also is a possibility that Naia's liver will fail completely, requiring a transplant. In the meantime, Hyams tells Greg and Tierney there's a good chance Naia needs a liver biopsy, a surgical procedure in which cells from the liver are removed for extensive tests and microscopic analysis.

When added to the looming heart surgery, the prospect of liver surgery, a transplant, or even a biopsy frightens and depresses Tierney and Greg.

Hyams also diagnoses the urinary tract infection, which requires Naia to take another antibiotic, amoxycillin. He prescribes vitamins K and E, and a multivitamin called Polyvisol. It fills another page in Tierney's medical notebook.

After days of fear and uncertainty, Tierney and Naia go to Hartford Hospital for a procedure in which a chemical is injected into Naia's body then traced as it moves through her system. If it doesn't pass from her liver to her intestine, a life-threatening blockage would be the most likely culprit.

To perform the test, a technician places Naia on a padded gurney, using straps to immobilize her under a machine that tracks the chemical. She screams and struggles, but eventually surrenders to sleep. Tierney also succumbs to stress and exhaustion, nodding off in a chair at Naia's side, her head down on the gurney just inches from her daughter's.

When they awake, the technician has the first bit of good news in what seems like a long time. The chemical passed into Naia's intestine; she doesn't have a blockage. ''Our prayers were answered,'' Tierney tells Greg when she and Naia come home.

Naia's jaundice remains an issue, but from that and other tests, Hyams concludes she most likely suffers from neonatal hepatitis. It is an ailment of uncertain cause -- possibly an infection, possibly some link to Down syndrome -- that will resolve with medicine and time.

No surgery, no biopsy, no transplant needed.

And soon, Naia's skin will begin to lose its yellow tint.

A casualty of their worries about the heart, the weight, and the jaundice is Tierney's effort to breast-feed. By mid-January she is no longer even collecting her milk and mixing it with the formula. ''I did the best I could,'' Tierney tells herself.

Left in the freezer are 15 glass bottles, each filled with four or five ounces of breast milk. Tierney doesn't want to dilute the thick formula, yet she can't bear to throw them out. So they remain in the freezer, until they spoil.

* * *

Back in August, when Greg and Tierney were choosing to have Naia, the most vocal opponents were Tierney's father Ernie and brother George. Now, both are trying in their own ways, with varying degrees of success, to heal the rift.

On his first visit with Naia, in early January, George steps into the role of favorite, and only, uncle. He holds Naia, smiling and laughing. When bedtime comes, he kneels by her cradle, rocking her gently and telling her it's time to sleep.

''I'm sorry,'' George tells Greg and Tierney. ''I wish I had never said anything.'' They embrace and forgive him.

Ernie, meanwhile, has expressed himself mostly with gifts, sending Naia a playpen for Christmas along with pants, booties, a yellow sweater, and several body suits. Tierney assumes the clothes were the work of Ernie's girlfriend, whose daughter runs a company that sells clothing for undersized babies.

When Ernie drops by on a business trip, he keeps his distance from Naia. He seems interested when Greg and Tierney describe her ailments, but he won't hold her. There is no change of heart, no apology for saying her birth would be a tragedy.

Ernie's rigidity makes Greg and Tierney wonder if his attitude reflects something more than race, something more than what he said about having a baby that burdens society and themselves. They wonder if her problems are stirring up painful memories of his own past.

Ernie's only sibling, his younger brother Norman, suffered from a severe birth defect. A kind and funny man, Tierney's uncle and godfather, Norman Temple was handsome. But only from one angle. The other side of his face was deformed, his nose and eye crushed like kneaded dough.

When Norman was a teenager, a surgeon attempted to repair some of the deformities by sewing his hand to his face. It was one of several painful attempts to grow new skin, and they met with limited success.

Ernie had looked out for his kid brother when they were boys, and he cared for Norman before he died of cancer in 1989.

Early in Tierney's pregnancy, before they knew about Naia's Down syndrome, Ernie made a comment that struck them at the time as strange but unimportant. It began when Greg asked Ernie if he had any advice or concerns about his unborn grandchild.

''Well, you're both physically fit, and you both have good genes,'' Ernie said.

Thinking back, Greg and Tierney are certain the message was: ''You don't want to suffer through our experience with Norman.''

''It's like that was the ultimate test for him, his ultimate fear,'' Greg says. Finishing his thought, Tierney says, ''And now it's come true, like a self-fulfilling prophecy, and it's difficult for him to accept.''

* * *

Slowly but surely, the heavy diet of formula takes effect. By Jan. 28, Naia weighs 6 pounds 13 ounces. On Feb. 11, she is 7 pounds 4 ounces. On Feb. 26, she is 7 pounds 8 ounces. Finally, by March, she reaches 8 pounds.

Still, her growth rate is troublingly slow, and her heart defect continues to tax her body. Hope that surgery could wait until late spring is cast aside. It will happen by April 1.

In the meantime, despite all her challenges, Naia has been growing into an individual in her own right.

She seems to recognize her name. She is starting to like baths, especially when someone sings ''Rubber Ducky.'' She has a favorite toy, a stuffed red Elmo doll, from Sesame Street. She follows objects with her eyes, particularly ones with bright colors and bold patterns. She sings out in little yelps. She smiles an innocent, toothless smile. Greg melts every time she gives him one.

A few days before Naia turns four months old, Greg tells Tierney: ''I think Naia is beginning to look a lot like me.''

''She's cuter,'' Tierney says, and they both laugh.

Tierney returns to work, having received a promotion and arranged a schedule that will allow her to work from home some days. Greg works at home on his doctoral dissertation and oversees daytime care of Naia -- with some unexpected help.

Just before Tierney's maternity leave ended, Greg's mother, Mary Fairchild, moved to Hartford from her home in Virginia. While Greg and Tierney remained in their old apartment, Mary settled into the new place Greg and Tierney had bought just before Naia's birthday. Greg's father will join her when Naia has surgery.

* * *

It is March 16, and Naia's growth has stalled again. The operation will be in two weeks. Today Greg and Tierney tour the surgery suite at Children's Medical Center.

Despite the setback, Tierney has been feeling confident about Naia's prospects. ''I am ready for Naia to be the Naia that I know she's going to be afterwards. Only occasionally do I think that maybe something will go wrong,'' Tierney tells Greg.

Greg, on the other hand, has grown increasingly worried. ''It's major surgery,'' he says. ''And then it's the idea of her having all that stuff attached to her. It's depressing.''

At the end of their hourlong tour, as they walk into the intensive care unit, Greg and Tierney notice a commotion at the end of the hall. Five doctors huddle, talking in low tones with grave looks on their faces. Just outside the doctors' circle, a young couple stands limp, sobbing and rocking and making feeble, futile efforts to comfort each other.

The tour guide hurriedly turns Greg and Tierney the other way.

TOMORROW: Heart surgery