|

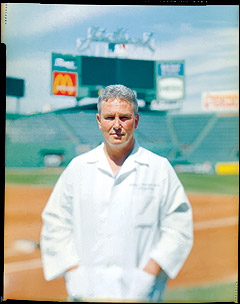

Bill Morgan (Photo / Christopher Churchill) |

Sox Doc

How does a doctor treat athletes worth millions of dollars? "Just like any other patient," says Red Sox team physician Bill Morgan. By Benoit Denizet-Lewis, 7/13/2003 |

|

Page 1 | Page 2 Single-page view |

ill Morgan doesn't like his car. Sure, it's a hot car, but hot doesn't necessarily get you anywhere on time, nor does it understand the orthopedic particulars of infielder Nomar Garciaparra's left wrist or pitcher Pedro Martinez's right shoulder or any other body part of earth-shattering importance. Morgan's car is an Audi TT Roadster, and if you've ever seen one, you know it can make an ugly man look downright appealing. Morgan doesn't need wheels for that (he has been accurately described, albeit by his PR person, as "the kind of guy women are attracted to and players want to have a beer with"), but he does need to get from Saint Elizabeth's Medical Center in Brighton, where he chairs the orthopedic department, to Fenway Park, where he serves as the Red Sox team physician. And right now, Morgan is behind schedule, stuck in traffic, and driving a moody car with a thing for mechanics.

ill Morgan doesn't like his car. Sure, it's a hot car, but hot doesn't necessarily get you anywhere on time, nor does it understand the orthopedic particulars of infielder Nomar Garciaparra's left wrist or pitcher Pedro Martinez's right shoulder or any other body part of earth-shattering importance. Morgan's car is an Audi TT Roadster, and if you've ever seen one, you know it can make an ugly man look downright appealing. Morgan doesn't need wheels for that (he has been accurately described, albeit by his PR person, as "the kind of guy women are attracted to and players want to have a beer with"), but he does need to get from Saint Elizabeth's Medical Center in Brighton, where he chairs the orthopedic department, to Fenway Park, where he serves as the Red Sox team physician. And right now, Morgan is behind schedule, stuck in traffic, and driving a moody car with a thing for mechanics.

Still, life is good for the pleasant, energetic 50-year-old with the curly gray hair, the pale face prone to burning, and the tanned arms and legs he attributes to his "Irish freckles coagulating, creating the appearance of a tan." Only 30 minutes ago, William J. Morgan successfully excised the contracted cords in the hand of a man suffering from Dupuytren's contracture, a genetic condition mostly affecting men of Celtic descent. (In a nutshell, your fingers start out fine, eventually lose the ability to straighten out, and finally, as punishment for being the kind of tough guy who never asks for directions and never goes to the doctor, get stuck in your palm). "Typical Irish guys," Morgan says with a laugh. "They blow it off for years while everyone is telling them, 'You know, you might want to get that checked out.' "

Today's surgery apparently went well, but it also went longer than expected. "One thing you can't rush in life is surgery," says Morgan, who often states the obvious as if he is breaking news. "It's not like you can stop and say, 'Hey, this has been great, but I've got a Sox game in two hours.' "

But Morgan does have a Sox game in two hours. And considering how players rallied around him recently, the good doctor has an extra incentive to get there early. On April 10, the Red Sox announced a three-year partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, making it the club's official hospital and health care provider. That would normally leave Morgan, on staff at Saint Elizabeth's, out of the equation. But Red Sox players, who lobbied hard for Morgan, are finally happy with their medical care after years of sporadic discontent with longtime medical director Arthur Pappas (Garciaparra once lamented loudly in the clubhouse, "When are we going to get a doctor who doesn't screw up the players?"). Particularly vocal were Garciaparra and Martinez, two guys whose opinion matter. So, while Beth Israel Deaconess now provides medical care for the Sox fans and front-office personnel, the players still deal with Morgan.

"Some of the guys apparently went to bat for me," says Morgan, who, in addition to often stating the obvious, has never met a cliche he didn't like. "And I guess the ownership listened. It's a lot different from the old regime, when the players weren't really asked their opinions about much of anything. But that's water under the bridge now."

organ pulls his Audi into the players' parking lot, stopping a few spaces down from a significantly larger Hummer. As Morgan walks through the clubhouse toward the training room (he wears a stylish suit, which he will soon remove in favor of his trademark red team jacket), Sox players welcome him with a chorus of "Hey Doc," "Wassup Doc," and one "Hey MoMaaaaaaan," courtesy of infielder Damian Jackson. "I have no idea why he calls me that," Morgan says with a chuckle.

organ pulls his Audi into the players' parking lot, stopping a few spaces down from a significantly larger Hummer. As Morgan walks through the clubhouse toward the training room (he wears a stylish suit, which he will soon remove in favor of his trademark red team jacket), Sox players welcome him with a chorus of "Hey Doc," "Wassup Doc," and one "Hey MoMaaaaaaan," courtesy of infielder Damian Jackson. "I have no idea why he calls me that," Morgan says with a chuckle.

In the training room, Morgan's first order of business is Johnny Pesky's monthly vitamin B-12 shot (Pesky suffers from pernicious anemia, an inability to absorb B-12 through the bowel). "Johnny can do it himself, but he likes when I give him the shot," Morgan tells me. The 83-year-old Pesky, who hit 307 in a 10-year Major League career, now works as the club's special assignment instructor.

Morgan rubs Pesky's left shoulder. "Yeah, warm me up, doc," says a smiling Pesky, who sits in uniform, his legs dangling from the edge of the training table.

"You been working out?" Morgan jokes, handling Pesky's thin left arm. "Look at all these muscles."

"Yeah, yeah," Pesky says. "My wife has bigger arms than I do."

The two banter for a minute, after which Morgan finally sticks the needle in Pesky's shoulder. "Thanks, doc. You're a gentleman and a scholar," Pesky says. "Now I'm going to go irritate someone else. I already sent [Tim] Wakefield running. He was in here relaxing, and I chased his ass out."

There is more than an hour until game time, and during the next 30 minutes, Morgan keeps busy with relatively mundane medical tasks: Jackson asks Morgan for the name of a pediatrician for his son ("Don't forget," Jackson tells him, "because my wife keeps bugging me about this"). Morgan confirms, with the help of a dermatologist, that a rash on outfielder Manny Ramirez's face is a simple case of dermatitis that he sometimes gets when going from hot to cold climates. He examines the finger of a front-office guy, who apparently injured it while bowling. Finally, he fails to fall for the shenanigans of jokester Kevin Millar, who intentionally kicks a table on the way out of the training room and yells, "Oww."

(It is still several weeks before Morgan will really have to earn his paycheck. In June, three pitchers have health problems: Martinez strains his shoulder, Casey Fossum develops shoulder tendinitis, and Robert Person injures his hip. Morgan also operates on two promising minor leaguers, including one who was injured during an on-field fight.)

As the game begins, Morgan

I've only known Morgan for an hour, but already I understand why players like him. He has a laid-back, youthful, frat-boy energy to him, but he combines it with a consistent aura of professionalism and intelligence. He comes off as honest. He is also polite and attentive, and he has the rare ability to make you feel as if you're the only person in the room. Most important, perhaps, he understands that his job is as much about psychology ("I have to get into the heads of these players") as it is about fixing rotator cuffs. And surprisingly (to me, at least), he treats minor leaguers, bowling-impaired front-office personnel, teenage pitchers, and stubborn Irish guys with bad hands with the same level of respect and care as he does Manny Ramirez. This endears him to just about everybody.

Tonight's game turns out to be mostly uneventful on the medical front, which Morgan says is exactly how he likes it. "Knock on wood, but this season's been a cakewalk so far," he says. I ask him where he learned to use two cliches in one sentence. "I learned it from the best," he says. "I've spent far too much time in baseball clubhouses."

ill Morgan was never much good at baseball. What he was good at was skipping classes at Boston University, spending his weekday afternoons at Fenway Park. "That made getting into medical school a little more challenging," says Morgan, who grew up in Dorchester and Quincy. He eventually went to graduate school at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston (where he met his former wife, with whom he has three daughters in their late teens and early 20s) and then to medical school at the University of Texas in Galveston. Intent on being a plastic surgeon, he returned home to intern at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester in 1981.

ill Morgan was never much good at baseball. What he was good at was skipping classes at Boston University, spending his weekday afternoons at Fenway Park. "That made getting into medical school a little more challenging," says Morgan, who grew up in Dorchester and Quincy. He eventually went to graduate school at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston (where he met his former wife, with whom he has three daughters in their late teens and early 20s) and then to medical school at the University of Texas in Galveston. Intent on being a plastic surgeon, he returned home to intern at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester in 1981.

There, he was turned on to orthopedic medicine by Arthur Pappas, then the professor and chair of orthopedic surgery at the Worcester hospital, the Red Sox team doctor, and a part owner. Like everyone who first meets Pappas, Morgan was taken aback by his eyebrows. They are truly extraordinary. Preposterously thick and bushy, they appear to take up half the available space on his forehead. Not only that, but the left eyebrow curves dramatically, covering a section of his cheek, as if being weighed down by an imaginary Christmas ornament.

"He seemed larger than life to me, and not only because of his eyebrows," recalls Morgan. "He just has this intimidating presence that commands fear in some and respect in others. And I think that because I was a little irreverent, he kind of liked me. We developed a father-son type of mentoring relationship."

Pappas says that Morgan stood out among the interns both for his personality and his medical ability. "There are plenty of orthopedic surgeons who are great technically, and Bill certainly is that, but most don't have the personal skills that Bill does," Pappas says. "He was a natural at this."

Soon, Morgan

Helen Robinson, who for years operated the park switchboard, didn't help matters. "In those days you couldn't call into the park or out of the park without going through her," Morgan says. "Everything went through Helen. So I call her on one of my first days, I'm nervous as hell, and I say, 'Hi, Helen. This is Doctor Morgan.' Dead silence. Then finally she says, 'Well, who the hell are you?' I say, 'Well, Helen, I'm Dr. Morgan. I'm covering the game tonight for Dr. Pappas, and I need to call UMass.' Silence again. 'Well, what the hell's the number?' she says. So finally she puts me through, and now I'm trying hard to make her like me, because I'm getting the feeling that this woman could really ruin my life here. I say, 'Helen, it's really a nice day out there, isn't it?' She says, 'Well, how the hell would I know? I'm half blind!' "

That same week, Morgan learned a valuable lesson for any team doctor: Don't mill around in the stands if you don't have to. "I was so excited to be here, I would get to the games four hours early and just walk around the park," Morgan says. "So I'm out in the stands, soaking it all in, and all of a sudden this guy comes up and says, 'You're the doc, right?' I said, 'Yeah, but I handle the players.' He says, 'Well, there's nobody around, and that guy over there looks like he's having a heart attack.' So I go over, and the guy's choking on a hot dog. I do the Heimlich, and the hot dog comes out. But now he's having chest pains. Back then, we didn't have defibrillators at the park, so we had an ambulance come. I ride with him in the ambulance, and all of sudden he barfs all over me. So now, of course, he's feeling better. I take a cab back to the park, and I have vomit all over me. That was the day I learned not to get to the park too early, and when I do, to stay in the clubhouse."

|

Page 1 | Page 2 Single-page view |

![]()

© Copyright 2003 New York Times Company |